I´m back in Europe this week.

This, in fact, is a bit weird because a few weeks ago I wasn´t even prepared for leaving the continent at all, nor Germany, nor Munich, nor the university campus until all exams are over. The steady rain periods in Germany had me decide to definitely delay the second part of my soaring season to the August competition phase to come. Little did I know my fortune had completely different plans for me.

I only remember my phone ringing one night, I recall a ten minute talk including lots of explanations, plans and names. Arcane names of places and things which I had once read about in infrequent, wonderful reports but never heard spoken before. I remember saying slowly, “I guess you know you´re making me an offer I can´t refuse”, and I remember the well planned and precise answer: “Yes.”

After that, things went really fast, fast enough for me to convert into a howling hurricane of studying, preparing, thinking, staring, packing, working, learning, calculating and not sleeping. This was amazing. Ridiculously awesome. Someone had just invited me to join a most unusual soaring expedition. I was going to be a safety pilot and mountain instructor for two weeks. I was going to go to Africa. I was going to fly in Morocco. I was going to go to Ouarzazate, the place nobody in the soaring world seemed to know anything about except that “There must be thermals like hell”, nobody except the extremely limited group of pilots who had actually been there.

You´re not in for a flood of information when you type “Ouarzazate” into Google, even less if you don´t speak French or Arabian, and even less less if you add the word “soaring” to your search. The only usable information for preparing some operations come from the Schmelzer family, who published an unspeakably amazing photo gallery about their 2012 expedition. Also some written content leaked to the Cafe by Tijl Schmelzer via Ritz de Luy. In one short report Tijl expresses that Morocco is the “best thermal activity region ´til now discovered”, a sentence which made my blood freeze ever since when it came to my mind, and Tijl´s sentences generally come to my mind very often.

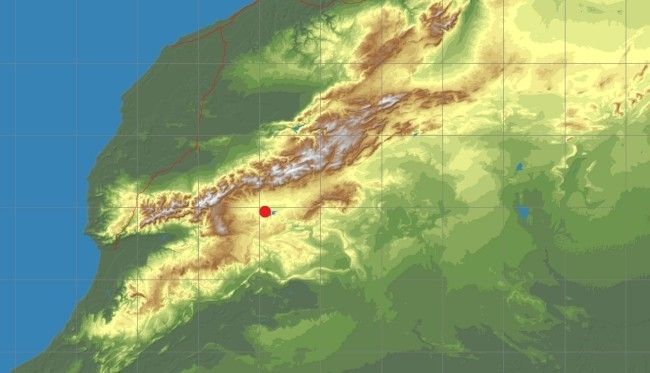

The main flying area from Ouarzazate is pretty obvious as the airfield lies close to the southeastern (=Sahara) side of the Atlas Mountain Range. Wherever there is heat and mountains, they must form a thermal induced pressure difference, ergo a breeze system, providing energy for thermal activity over the high terrain. I like to call this principle a self sustaining thermal system. And wherever there is one, I want to fly in it.

The fact that I was going to go soaring in Morocco in a few days wasn´t the only awesome fortune these days. The other one was that my good friend Tim Sirok called me one evening, telling me in an overly excited manner that he had spontaneously been invited to coach in an EB28 in Ouarzazate. I needed some time to stop laughing until I could tell him that the exact same thing had happened to me. We compared our flight dates and found out that we would meet in Africa in only a few days time. This was just too good to be true.

Not long after that, we were there.

Ouarzazate is a midsize town in the outskirts of the Sahara Desert. It is also in the outskirts of the opposite High Atlas mountains, which means that it is in between two very large places without anything going on. Ouarzazate is in the middle of nowhere.

They have an international airport, though. At 3000 m by 40 m, its runway is mindblowingly large. Twice a week there´s a commercial flight from Casablanca, sometimes even from Spain, bringing small groups of transmigratory tourists to the starting points of their Sahara desert trips. We also met a few international travellers with light aeroplanes at the field, but most of the time we were alone. Still autorities are present to the airfield 24/7 so that we had to follow the standard security procedures whenever we wanted to approximate our gliders.

My pilot was Konrad Maierhofer, who had brought his DG505M-22 to Africa by trailer. Konrad is the executive of the Fly Down-Under Soaring Center in Stonefield, South Australia, where he had invited my team mate Fabian and me in 2011 to find out about Stonefield´s Cross-Country potential and to prove that 1000 km could be done there from a winch launch in a Standard Class glider. Here in Morocco he hoped to benefit from my Australian desert and European mountain experience, combined in one single complex soaring area.

Tim´s pilot, co-owner of their ASH25 EB28, was Kurt-Jürgen Bock. Of course the two of them had similar objectives to Konrad´s and mine: Learn a lot, see a lot, get to know the area, and then go for the famous four digits.

The first few flights gave us a taste of what was happening in the Atlas. In higher altitudes we had westerly winds bringing relatively cool and stable air from the Atlantic Ocean. This limited operation heights to about 4500-5000 m at first, which sounds a lot but can limit your decision envelope a lot if the terrain is 3000-4000 m high and you are in the area for the first time. We got trapped in a few tricky situations during the first flights which got us onto really thinking through strategy and flying very careful as long as this weather prevailed. Still, the flights got us about 600 km through the area each, giving us a perfect general view of how to do it. Even though pure mountain flying theory is applicable at its very best in the Atlas due to the clearly arranged terrain, I had to learn how to believe in the things I had learned in all these years.

The sun is mostly vertical during large parts of the day so it was finally time to entirely forget about all the “which-side-is-facing-the-sun”-thinking which often leads to mayhem in the Eastern Alps as well if you don´t consider local heat/pressure distribution and breeze circulation along the canals/valleys. I spent a lot of time close to the ridges, sometimes below the peaks. In the beginning because I was forced to, in the end because I knew it was the best imaginable place to test the theory. After only two days in the Atlas I had found plenty of proof to what modern alpine soaring theory talks about.

As soon as the high winds got weaker and ground winds started to turn to east, we were in for the first bigger thing. We did not have the 1000 km route figured out completely yet and were not sure about a few routes on the way northeast. Tim and I had spent an evening giving the most important mountains our own names to help us memorize every detail about the decision points in the terrain. This technique had helped us a lot in France in the past, although we have long since gone over to use the real french names.

The day was not quite a very good one. Like the days before, we had to work for more than two hours in the blue before the first Cus popped up in the northeast. I hardly ever let go of the direct contact to the mountains, partly because I wanted to, partly because there was no way to exceed 5000 m anyway. However, the work of the past days helped us a lot on our way along the Atlas range.

We knew all the long lines and options for speedways, we knew the emergency exits, we knew the points of no return and the tactically suitable potential turnpoints. When the Clouds at the northeastern end of the Atlas Mountains improved we decided to give the 900 a shot. We left the mountains for the first time and proceeded to km 310 from Ouarzazate. We turned at a creepy five pm.

The way back into the higher terrain worked well but we could feel the conditions deteriorate. There was no way to maintain our 130 average which we had had during the last two hours, but I tried to keep cool calling into mind that this wasn´t even necessary when sunset was only at 8.30 pm. We still had plenty of time.

140 km out, the sky turned completely dry and blue. The last cloudbase finally topped 5000 m but Ouarzazate itself is at 1140 m, so that everything sounds a lot more than you actually have. There were still about 800 m lacking for a safe final glide.

After a long glide through dead air and an even longer discussion whether we should leave the mountains on direct course or head along the main ridges for just a bit more before heading into the desert, we finally found some energy lines and some weak climbs. It turned out that the lower layers of air were still highly convective until sunset. This was great to know for the days to come, and when we set the wheel on the 3000 m concrete strip at sunset, we had done just a bit more than 900 km.

The next day was the first one without maritime airmass at altitude. We had high expectations but were disappointed by 70 km/h of wind in the upper layers. Although thermals were very strong I considered them unusable so we decided to focus on getting into wave. Entering the M`Goun wave was a lot easier than anything I was used to in the Alps due to all the supportive rotor thermals. Unfortunately we had only signed a flight plan to FL 195 and could not get permission to climb higher via radio although there was no traffic in the area. I didn´t dare to go crosscountry in potentially blue wave in a terrain I knew from four days of thermal flying because I had to prepare for successful wave crosscountry flying in European terrain for a couple of years and didn´t want to underestimate African conditions. So we aborted the flight and went to spend the rest of the afternoon preparing for the next days.

Two days later, we were in for the 1000 km race. The wind had finally brought hot desert airmasses throughout the convective layer and had weakened enough to permit normal thermal systems to develop. I remembered my first 1000 km flight in Australia and how I couldn´t make it to start altitude until 12.20 pm there in the blue, and having to fly an outrageous race against time all day to get home not even at thermals’ end but at sunset. Until the last hour of the flight I had no idea if I could possibly make it. This had had a lot of thrill in it, but it ruins a lot of the potential of really big days. That´s why I burst into wild laughter that day in Morocco when after turning off the DG´s engine at 10.30 am near the start point we had worked out, we worked our way into the high terrain and found more than 2 m/s of climb from the beginning. From the first lift on, time was on our side – a completely new feeling for me at long-distance attempts also in Europe.

The atmosphere was much hazier than in the past days because the desert air did not only bring heat and instability, but also heaps of sand to the Atlas. It was hard to make tactical decisions at first because it was impossible to see more than two clouds ahead. Maintaining high speeds would have been impossible without the experiences of the past week. Still it was a major surprise to find something was kind of weird with the air on the second leg at about 3.30 pm. Coming closer we saw a huge CB, one of the broadest and highest storms I had ever seen, coming out of the dust. Visibility went back to 5 km in its direction. After a short discussion it was clear we would not make it through, nor past, nor anywhere but back where we came from, back away from Ouarzazate, back northeast. It was clear that the only exit for the homebound leg was going to be the southern route over the Sahara Mountains, a smaller chain of hills about 80 km south, which we could guess was kind of developed through the haze.

After making sure there was definitely no rain in the south, we backed northeast again to set another turnpoint in the good area we came from. Unfortunately the showers influenced the whole area so much by now that the climbs deteriorated rapidly. I have seen a lot of storm and shower development in my life but have never experienced anything weatherwise happening so fast and spreading so broadly. We decided to go south, and to go NOW. The glide was long, and I was uncomfortable leaving the mountains to an area I had never been before that I could not even see because of all the sand in the air.

Luckily, the 22 m of wingspan were enough. The exploding Atlas air created lots of rapidly cooling air which produced a major outflow from the high terrain, which we were (un)lucky enough to sink into. With 40 km/h of wind in the back, we could make it to the first developments over the Sahara Mountains. It was half past six now but the short leg back northeast and the long tailwind glide south had given us plenty of kilometers so that we were still on track. At closer look, the sky on course looked really promising. We connected with the first cloud of the street and fired upward with more than 3 m/s. This lift to almost 5500 m turned the whole situation upside down, because everything changed from “Are we going to get home at all?” to “Looks like we almost made it!”. And that was it – the rest of the flight consisted in some more booming evening lifts and a bit of OLC optimization strategy. It was Konrad´s first 1000 km and I was really proud to have learned to deal with the area in only six flights. But we were not done yet.

The last flight topped everything I had seen so far about soaring conditions on this planet. It was not quite as thrilling as the one before, but still a challenging one. The early launch worked even better than before and we were on track at 10 am. After only 120 km on the standard route things started to turn blue and tough again, and I had the burning feeling that we were just too early on this one. So I decided to give the first turnpoint away already and head back along Goun where we had felt roaring conditions in the morning. It was definitely worth the trial because as soon as we turned, we made 1000 m of altitude without flying a single circle as we saw the sky in front of us explode with convergence clouds. We had never been southwest before but I had learned the terrain on the map so that we were able to make good progress without losing our situational awareness. Face to face with Toubkal, Morocco´s highest peak (4167 m) we turned back north, hoping for the blue hole to have developed by now. It was half past two, but already the convergence line started to massively overdevelop all the way we had come. We could literally see a wall of dust, rain, ice and sand form over the main divide of the mountains. Still, we were able to feel the energy in the air and followed a line we found intuitively under the rapidly spreading cloud cover. There were a few situations when we didn´t know what was around the next corner, but it was way more comfy than the day before because we always had final glide height to Ouarzazate and from the last flight we knew that the desert side would start to work as soon as the Atlas system collapsed.

It didn´t collapse until we were off and away northeast on the standard route, which had developed just fine during the hours we had spent in the southwest. Our plan had worked out perfectly.

The second part of the journey was similar to the flight before: we turned south as soon as we saw the Atlas ultimately closing down its thermal business behind us due to all the exploding OD´s. The Sahara mountains worked even better than last time. But even they had an overdevelopment tendency in them – I guess there was just too much energy around even though the atmosphere almost totally lacked humidity. This is why we landed an hour early after 1090 km – the showers had just made the whole scenery too confusing.

It was good to land early for me anyway because this was my last day and the only way for me to safely catch my flight from Marrakesh the next morning was to take the night bus. So I landed after the biggest flight I had ever done at 7.45 pm, went to the hotel, packed my stuff, had dinner with the whole team one last time and headed off to the bus stop a 11 pm, to spend the night riding an outrageous bus through an outrageously dark and deserted area. I could not find any sleep, knowing that this was probably the most outrageous day I had ever spent anywhere in the world.

I have taken lots of pictures during all the flights. You can watch the whole photo gallery here on my own blog, flugfieber.net .

You can see Tim´s wonderful photos here.

2 comments for “Tea with “Two-Delta” – News and Views from North Africa”