Thanks to Gary Osoba for sharing the first chapter of his book, Born to Fly (in progress). For many years, Gary has explored the realm of dynamic soaring, where soaring flight is sustained in light and maneuverable aircraft by extracting energy from wind gradients and convection near the earth’s surface. In the process, Gary has earned many national and world records in ultralight sailplanes. We look forward to the publication of his book — The Editors.

BORN TO FLY

“ The shortest distance between two points is a straight line.”

It was the 1960s, and I suppose that it was my first brush with philosophical debate. That is to say, something I participated in, even silently. For here was something I had knowledge beyond my years in, and something that I really cared about.

My Uncle Joe was one of the most wonderful people I have ever known. Tall and stately, and in so many ways the southern gentleman. Such a kindly manner and a broadly developed sense of humor which endeared him to all he met. And a deeply abstract thinker. This quality, misinterpreted frequently as absent-mindedness, was what led to many close scrapes when traveling down the highway to his ranch… dawdling along … some 20 or 30 miles per hour below the speed limit … traffic bending and roaring past. Here he is in the center of the lane, now he’s using the shoulder … now he’s using the other lane in a momentary excursion.

Lines and arbitrary limits didn’t mean much to Joe, especially when he was thinking hard about things.

I recall having dinner with the retired Chairman of the Board for Exxon, at a time when it was and had been for some time the largest corporation in America. Seated there in the country club of Bryan-College Station, he unwound several stories like a thread unspooled. Yes, Joe had been with Exxon for quite a time between his teaching posts. He was in charge of reservoir engineering, a highly complex 3-dimensional analysis, not unlike weather forecasting but without the ability to directly measure many of the important parameters. He said that whenever they would come up with a particularly enigmatic problem anywhere in the world, they would supply Joe with all of the available data but no interpretations. He would then retire to the privacy of a secluded room for several days and begin absorbing things. Outside life would go on, bending around him like cars on the highway. Slowly, and most often without some logically developed method which could then be demonstrated, Joe would arrive at the answers. After some new discovery, he would then trace the steps backward in order to prove and refine the conclusion mathematically. He was able to grasp the very essence of complex physical events, grapple with the unseen reality, and somehow transform it into communicable thought.

I suspect that similar paths were taken during other endeavors, although I never heard much about these. His other doctorate was in nuclear physics, and he knew the geniuses Einstein and most particularly Fermi, with whom he worked closely during a difficult time in this nation’s history. The small band of scientists which assembled in Chicago had embarked upon one of the most sober of all investigations to date. Joe was often described as a genius himself by his contemporaries.

So it was when he railed against the environmental efforts which prevented oil and gas exploration along the coast of Texas, he was a formidable advocate.

Grus americana. The Great White Crane. “Garoo.”

Whooping Crane. My childhood fascination with birds and flight had led me into many considerations, and some of them were serious. Most researchers said there were only 21 birds left in the world. Others, even less. What they all agreed upon was that the sole remaining wintering grounds of the Whooping Crane were located above a rich hydrocarbon deposit and that it must not be disturbed. The idea of a species, precariously perched upon the cliff of extinction, was something relatively new to my young mind. And, it was scary.

These were not unfounded fears, for the 20th century had seen other sad examples. The Ivory-Billed Woodpecker… gone! The Passenger Pigeon – once the most numerous of birds on the North American continent…gone!

So large were the migratory flocks of these birds that Audobon once wrote the air was literally filled with them, and the “light of noonday was obscured as by an eclipse.” In the autumn of 1913, he estimated the size of one flock which was a mile wide during a 3 hour passage. Covering a mile a minute, allowing 2 pigeons to the square yard, they numbered 1 billion, 115 million, 136 thousand. He must have tired of observation after 3 hours, because this retinue continued for 3 days while he traveled a distance of some 55 miles.

Alexander Wilson, widely regarded as the father of American ornithology, once described another flock of a mile’s width, this one 240 miles in length.

It numbered 2 billion, 230 million, 272 thousand birds… enough to eat an estimated 17,424,000 bushels of nuts and acorns daily. In 1806, these commodities must have seemed as important to man as hydrocarbons are now to our automobiles.

So it was that Uncle Joe and I disagreed, me doing so silently out of respect. It was actually a wonderful learning experience, and I filed it away with lots of other Uncle Joe memories for future awakening.

2000. Shortly after the advent of the new millennium, a friend who is a writer phoned.

“Are you aware that you hold more general category world records in gliders than anyone at this ‘momentous’ time?”

“And how do you feel about it?”

I was aware, but assured him that this coincidence had much more to do with the fact that I enjoyed flying unusual types of gliders than it did with pilot acumen. Not exactly a lot of competition, in other words. However, it must have meant more to me than I thought because later, when informed that pilots from the former Soviet Union and eastern Europe were aggressively after some of these records, it caused a real stir in me. It wasn’t so much the defense of the records, or any nationality (which makes no difference whatsoever) as it was enjoying a good challenge. “Le cœur a ses raisons que la raison ne connait point.” *

* The heart has its reasons that reason knows nothing of.”

So here I was in Hearne, Texas. Just a few miles from Bryan-College Station and even fewer miles from Uncle Joe’s ranch where I spent many summer months working as a young teenager. Needing to set three new records in a short amount of time. The memories kept flowing forth out of the cornucopia of youthful impression. The smell of the air in the pre-dawn landscape. The humidity. The giant orb weavers, hung still as an ornament among the foliage … the most sublime of yellows in the dawning light! It was all more familiar than impressions which may have been only a week or two old. Such is the potency of youth, aged in time.

Notably, there was that same dynamic sky with predictable patterns. The relatively good conditions were only part of what brought me here during the limited time I had available to attempt record flying. The other half of the equation was the generous invitation of an ultralight and hang gliding flight park operator. He and his fiancé were hosting a large regional championship and were happy to provide aerotows for the very light glider I would be flying.

My plan was a simple one. Feel out the air the first day of flying, and then attempt records for the remaining 3 or 4 days. After getting acclimated, I decided to fly an out-and-return course on my first official attempt. The competition director had called a long downwind task for the hang glider pilots that day. If I could fly downwind to the distant turnpoint and then double back on my course, returning to where I started, it would be a sufficient distance to set a record.

The early going was slow because the conditions were late to start. Additionally, there were some broad blue areas about 20 miles into the turnpoint which had to be traversed twice … once going out and once upon return. Even so, I had successfully negotiated these obstacles and started passing the field of hang glider pilots on their one-way journey while I was on my return leg.

Of greater concern was the wind factor, which makes out-and-return courses in relatively light gliders difficult when flown over the flatlands. Along mountain ranges or coastal ridge lines, a perpendicular wind will produce lift without the penalty of a headwind on one of the legs. In heavier gliders at higher cruise speeds, a typical head or tail wind produces a relatively smaller horizontal component and is therefore not much of a factor even over the flatlands. But going out in the light glider on my initial leg, I had experienced a 15 mph tailwind component. This would now be turned into a headwind on the return course, slowing progress and reducing my effective glide ratio over the ground. This factor amounted to about one third of the glider’s 48 mph airpseed for best glide. More climbing would be required for the distance covered and while climbing, the wind would be blowing me backward along the course and costing me precious miles and minutes. Record tasks are all about time, and the clock was ticking away.

Another difficulty was developing. A large region of atmospheric instability had spiraled up from Hurricane Beryl in the Gulf. Throughout the afternoon, a building wall of overdevelopment became apparent to the south and west. There were also smaller, localized trends of overdevelopment scattered through the region. One of these was located a little bit east of my course line and I avoided it. However, as I flew closer to my finish point the effects of the large line of buildups could not be ignored. The towering columns of imbedded thunderstorms had cut off the afternoon light, completely shading my return course and extinguishing the few remaining thermals. I was 16 miles out from my goal, the outflow from the storms had increased the headwind component to 20 mph, and much precious altitude had been lost as the thermals became scarce. I was desperately in need of one more climb. If I could find it, and climb as high as possible, maybe, just maybe I could manage my losses on the final glide in such a way as to squeak back in.

Feeling my way through the nearly lifeless sky, I stumbled first upon an area of reduced sink. Then, quickly responding to the lateral variations, followed a string into neutral air, then mild lift, then more abrupt turns and increasing lift. Finally, I contacted the heart of an honest, smooth thermal… surely the last one of this day over increasingly darker terrain! After such a long time between climbs, I resolved to stay with it as long as I possibly could. This would be my only hope of making it back.

After centering the thermal and returning to the reasoned climate of analysis and decision, I caught sight of 3 geese climbing in formation about 500 feet above me. It always makes me feel good knowing I’m not alone in a thermal, and especially good when the masters are present. Shortly afterward, I lost them and continued with my work. The southern part of the thunderstorm was building considerably, and numerous lightning strikes were now visible against a black wall of rain. I could see my final destination in front of the storm, but had increasing doubts about whether or not I would get enough altitude to make it. I had drifted back to 17 miles from goal and the headwind had now increased to 22 mph.

It was then that I saw them … unmistakable in the reducing light.

The striking patterns of white and black, the scarlet markings of the head which appeared to glow from a fire all their own.

There is no other bird on the continent which looks anything like the Great Whooping Crane in flight. The long, outstretched neck may appear goose-like from a distance. But cranes are massive, and cranes in soaring flight possess a majesty which is hard to describe to a person who has never seen one. The Sandhill Crane is similar in form, but the inky black wing tips and surpassing grace of the Whooping Crane are uniquely distinctive.

Due to the size, they must have been more like 800 feet above me when I first sighted them… and now I was at their level. But why were they here, at this time? How could they be this early, in August?

The ensuing moments may have been only that. Or they may have been minutes.

Hours wouldn’t have mattered while we were lost in the folds of time.

Me on my side of the thermal, they on theirs. Juxtaposed.

Locked together in a timeless stasis, while everything else rotated in exceedingly slow motion.

I was awakened by the realization that my habits had separated me from the path. Unconsciously, I had begun to climb through them. The mirrored structures now shattered, they were no longer immune to gravity and yielded in an instant. Chaotic shards disappearing earthward.

It was over.

But there was still a decision to make.

How could I continue to climb through them? Having experienced what I had, knowing what I did about them? How could I? There has never been a consideration with hawks or other birds, even eagles. Maybe the converse has been true… an incentive to climb faster! But this was different, knowing what I did.

How could I?

Like a child peering upon the mirrored scene of a rotating music box, two dancers forever locked in position, a sparkling quality permeating the sound and the light.

A sense that this could be the departure point for parallel universes… that this one, of its own, could continue on forever.

No … does go on forever,

unchanging,

undisturbed.

I was circling at 6600 feet, and with the headwind my maximum glide ratio would be reduced from 24:1 to 13:1. The best case scenario would only provide 16.25 miles and I needed 17… actually, more than that to allow for the subsiding atmosphere which had now developed. There appeared to be another thousand feet of climb available below the clouds. Would that even be enough? I had resolved earlier to get every inch of it. Every fraction of an inch.

But how could I climb through them?

Soaring is all about decisions. The right ones. At its finest there is only one successful combination of events, the decisions depend upon a multitude of interpretations, and they must be made quickly. Sometimes, the decisions become value judgments. It is then that soaring becomes something like a trust.

I made this decision quickly. It was an easy one. I would not climb through them. I would deal with what remained of the flight in situ, spontaneously. There may be another path. If not, I was prepared to deal with the consequences of not making it home and landing short somewhere.

As things turned out, there was a path to follow. With heightened sensitivity, I followed a sinusoidal course of reduced sink to the airfield. Came in with an extra thousand feet or so, and plenty of speed once it was apparent that I would make it. As I flew over the finish point, setting the record, the encroaching storm from the south made its presence known more fully. A microburst had issued forth like a mighty lion’s roar. The dust cloud was moving toward me very quickly and was only a few miles south of the field. I deployed spoilers, spiraled down at high speed, and rolled to a stop just in time to jump out of the cockpit and steady the glider as the gust front hit.

It was about 60 mph, and soon there were a couple of helpers who rushed out to lend a hand. After a while, the high winds had passed and the glider was rolled to the tie down area, undamaged. I retired to the solitude of reflection and post-flight analysis.

Who can say why we do what we do? Sometimes there are elements which are easily traceable. Other times nothing can be found with the best magnifying glass. One thing, however, became crystal clear in this case.

Had I continued climbing, eating up several extra minutes in the process … continued climbing, taking the shortest strategic line between two points … climbed as high as I could, like cross-country theory dictates … done what was expedient … then, without fail, I would have encountered the 60 mph winds on my final glide.

And never made it home.

It is now known that the gravitational field of a massive object can bend light, space and time.When this occurs, the straightest line between distant points must follow a curved path.

Somehow, I think Uncle Joe would have understood.

About the Author

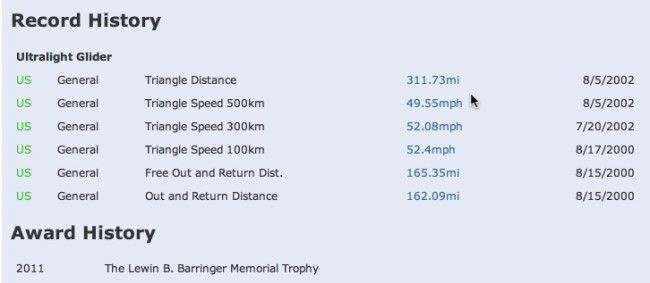

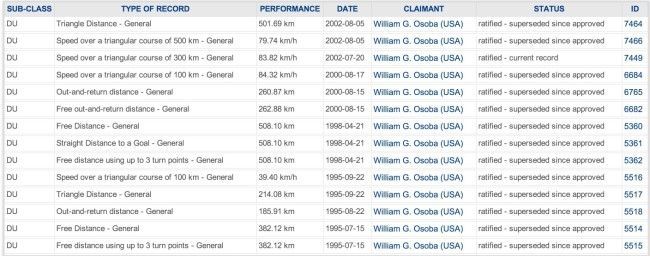

For more than two decades, Gary Osoba has been an active pilot, record holder, writer, and innovative thinker in the soaring community. In the late ‘Nineties and early 2000s, he set many U.S. and world soaring records in the ultralight category. In 2011, Gary also won the SSA’s Lewin B. Barringer Memorial Trophy, which is awarded annually to the pilot who makes the longest straight distance soaring flight in the U.S. that year.

Here are lists of his many records from that era.